Here’s another pop trivia quiz for all you detective fiction mavens out there. Earliest girl detective in the genre? Don’t even think Nancy Drew, gang. Go back further. Violet Strange -- did I hear someone say? Even further than 1915. Try the turn of the 20th century, 1899 to be exact, and meet little Gracie Death (yes, Death!), all of 12 years old and one of the pluckiest girl sleuths in the literature. Gracie pulls off some of the most dangerous legwork in Samuel Boyd of Catchpole Square (1899) while engaged as first mate to Dick Remington’s captain on what Remington dubs their private voyage into criminal detection. She also locates her missing father and does so by a combination of surreptitious eavesdropping and communication via her dreams. Yes, she’s not only one of the youngest and earliest girl detectives she’s also one of the earliest psychic detectives. And to top it off she does all this while suffering from a debilitating unnamed respiratory ailment (probably bronchitis or severe asthma) that often has her coughing her lungs out in a pitiful display. Time for Gracie to be recognized for her achievements. Cough or no cough she gets the job done.

Crammed into these 465 pages author B. L. Farjeon relates the murder of the odious moneylender Samuel Boyd who puts to shame Ebenezer Scrooge and Uriah Heep in terms of miserly opportunism and heartless avarice. Compounding the mysterious strangling death of Boyd is the disappearance of his clerk Abel Death, Gracie’s father, who was summarily discharged by Boyd several hours before his employer was sent off to his just reward. And the grounds for the firing? Death was caught dissembling about a visitor to the business, a direct violation of Boyd’s paranoid command to keep out everyone unless he is present. When Boyd learns that the visitor in question is his son Reginald whom he has practically disowned he lets loose with a tirade unparalleled in sensation fiction and fires Death on the spot.

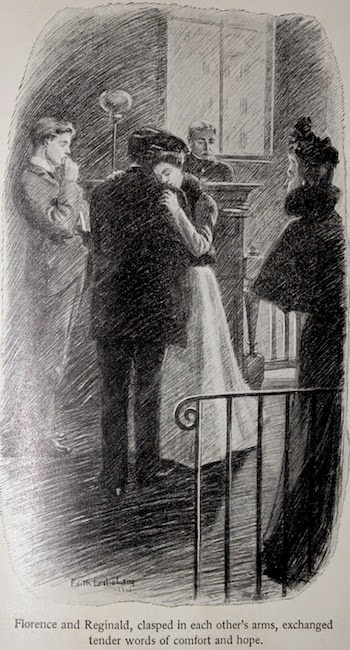

Dick Remington who we think will be the heroic detective of the piece is introduced as a young Renaissance man who has tried and succeeded in a variety of trades from professional actor to yeoman journalist, but suffers from ennui and a sense of being unchallenged with each new success. Only when he decides to clear Reginald Boyd of the murder charge does he find that he has true purpose in life. Reginald also happens to be rival in affections for Florence Robson, daughter of Dick's foster father and uncle Inspector Robson. This fact that serves as the primary motivator for Dick to perhaps win the affection of his cousin while simultaneously giving him another chance to prove himself worthy in the eyes of his Uncle "Rob". In true Dickensian style Farjeon has Reginald and Florence grow deeper in love with each new plot complication. Dick must decide if his adventure in amateur detective work is self-serving or selfless. Meeting Gracie Death alters his objective. When they join forces it is clear that Dick is beginning to mature in ways he thought previously impossible.

While the book begins as a puzzling detective novel Farjeon soon reveals the villains behind a massive conspiracy to frame both Reginald and Dick for the murder of the moneylender. Thankfully Farjeon does this by the midway point for the villains are so obvious the reader wonders why the police and everyone else can be so easily taken in by their machinations. Gracie isn't taken in but, of course, no one is going to believe a 12 year old girl. Except Dick Remington, that is. From its perfectly archetypal opening in which the characters are at the mercy of a menacing London fog to the perilous derring-do of Dick climbing a brick wall with rope and grapnel hook to the underhanded sleuthing of Detective Dennis Lambert of the Yard Samuel Boyd of Catchpole Square contains all that any reader has come to expect from a gaslight thriller.

With the revelation of the diabolical duo Samuel Boyd… becomes an all-out suspense thriller complete with cleverly handled courtroom sequences. The murder case becomes a cause célèbre attracting the attention of everyone in town including "members of the learned profession", actors actresses, writers and other celebrities along with merchants, housewives and their children. So crowded is the courtroom that some of the witnesses have to be escorted in from the hall. First we get a protracted inquest that frustrates coroner John Kent to distraction. The proceedings are hampered by a far too inquisitive jury member who is being goaded into asking intrusive, inappropriate and barely legal questions of several witnesses in order to sway the verdict towards implicating Reginald Boyd as the murderer. The novel ends in a climactic murder trial with the typical eleventh hour revelations including testimony from a French detective searching for an escaped master criminal and the unmasking of two characters’ dual identities.

One of the most intriguing incidents in the book from a history of the genre standpoint occurs when the two villainous doctors are fiddling with a newfangled camera of Dr. Pye's invention (see the illustration at left). It requires a strong burst from a magnesium flare and can illuminate the darkest unlit street from his second story study window. He has been photographing Samuel Boyd's house and has been seeing rather mysteriously the appearance of a face that resembles Boyd's even though he is dead. Pye then relates an anecdote about how useful and powerful the camera can be, especially in terms of "psychic photography". He asks his cohort, Dr. Vinser, to believe that a photographer friend of his used the camera to take a picture of a murder victim and when studying the photograph "...there under the lens of a powerful microscope was the portrait of the murderer upon the pupils of the dead man's eyes." The retained image, usually involving the retina not the pupils, on a corpse's eyes is a myth that shows up in late 19th century and early 20th century crime and detective fiction well into the 1930s, but this is the earliest recorded version I've come across. Apparently scientific fact is not the primary concern of these two doctors. But credit is due Farjeon with making these two doctors charlatans so we'll never know if he intended this sequence to be taken as satire of the gullible Victorian mind. Soon enough the reader learns the two men use phony titles to exert authority over others and have no background in medicine or science of any type.

But lapses into scientific myth aside if there is anything legitimate to criticize about Farjeon’s storytelling and writing it is his tendency to elevate his heroes and heroines to the status of sainthood while consigning his antagonists to behavior just shy of a mustache twirling and sneering vaudeville villain. From his very early career Farjeon modeled his work after that of Charles Dickens and we see in this late novel (he would write only three more books before he died in 1903) how he still aspires to the kind of triumphant overturning of detestable villainy by the virtuous and pure that was the hallmark of his idol. Rather than light touches of the sentimental paintbrush Farjeon slathers it on with sweeping broad strokes. Modern readers cry out for complexity and ambiguity in characters and incidents. You'll find no subtlety here. Even Dr. Vinsen, the more interesting villain of the two and seemingly modeled on Count Fosco ("My heart is large," says Vinsen obsequiously. "It bleeds for all"), has a sudden transformation within the span of a few sentences from sinister Machiavelli to cringing coward. But then sometimes it’s a welcome and refreshing change to know exactly who ought to get a rotten tomato thrown at him amid all the boisterous cheering for the good guys.

Benjamin Leopold Farjeon led a vivid and colorful life born and raised in England, travelling to Australia where he began his writing career as a yeoman reporter and eventually working his way up to business manager of Otago Daily Times in Dunedin, New Zealand. He deserves a post all his own on his fascinating life. For an overview see this richly detailed biographical article at TE ARA, the internet encyclopedia of New Zealand. His writing career was just as richly varied and includes short stories, ghost and detective fiction, plays, a very original and modern supernatural thriller called Devlin the Barber, Newgate novels, and a series of mainstream novels that are among the earliest to denounce anti-Semitism and present Jews of Victorian England in a positive light. Early in his writing career he reached out in a letter to Charles Dickens, his idol, and sending him a copy of his "Shadows on the Snow". Dickens replied and so moved was Farjeon by Dickens' letter he literally packed his bags, resigned his job at the New Zealand paper and headed back to England to become a novelist. All of this can be read in an absorbing interview Farjeon had with Dicken's granddaughter Mary Angela Dickens in the February 1899 issue of Windsor Magazine, published only a few months before the book edition of Samuel Boyd... was released.

Those interested in reading Samuel Boyd of Catchpole Square have their choice of a variety of print on demand books (be warned of optical recognition transfers littered with typos!) and a couple of online versions that I investigated which conversely look to be well done. Copies of the actual book currently for sale are few and far between. I know that there were at least two editions in the UK from Hutchinson and one in the US from New Amsterdam Book Company. My copy is offset from the New Amsterdam edition and published by stalwart reprint house Grosset & Dunlap. It includes four glossy plates by Edith Leslie Lang, some are used to illustrate this post. Should you be lucky to find one a reading copy of Samuel Boyd... should cost you no more than $10 to $15 compared to a genuine UK first edition (Hutchinson, 1899) which in good to very good condition ranges from $46 to $150.

For an entertaining Victorian viewpoint of B.L. Farjeon's writing straight from the reader's pencil see this post on Curt Evans' blog where he shows us the written remarks made by a Victorian gentleman in his copy of Farjeon's other mammoth sensation novel Great Porter Square: A Mystery.

* * *

Vintage Mystery Reading Challenge update: L4 ("Man's name in the title") on the Golden Age card

Crammed into these 465 pages author B. L. Farjeon relates the murder of the odious moneylender Samuel Boyd who puts to shame Ebenezer Scrooge and Uriah Heep in terms of miserly opportunism and heartless avarice. Compounding the mysterious strangling death of Boyd is the disappearance of his clerk Abel Death, Gracie’s father, who was summarily discharged by Boyd several hours before his employer was sent off to his just reward. And the grounds for the firing? Death was caught dissembling about a visitor to the business, a direct violation of Boyd’s paranoid command to keep out everyone unless he is present. When Boyd learns that the visitor in question is his son Reginald whom he has practically disowned he lets loose with a tirade unparalleled in sensation fiction and fires Death on the spot.

Dick Remington who we think will be the heroic detective of the piece is introduced as a young Renaissance man who has tried and succeeded in a variety of trades from professional actor to yeoman journalist, but suffers from ennui and a sense of being unchallenged with each new success. Only when he decides to clear Reginald Boyd of the murder charge does he find that he has true purpose in life. Reginald also happens to be rival in affections for Florence Robson, daughter of Dick's foster father and uncle Inspector Robson. This fact that serves as the primary motivator for Dick to perhaps win the affection of his cousin while simultaneously giving him another chance to prove himself worthy in the eyes of his Uncle "Rob". In true Dickensian style Farjeon has Reginald and Florence grow deeper in love with each new plot complication. Dick must decide if his adventure in amateur detective work is self-serving or selfless. Meeting Gracie Death alters his objective. When they join forces it is clear that Dick is beginning to mature in ways he thought previously impossible.

While the book begins as a puzzling detective novel Farjeon soon reveals the villains behind a massive conspiracy to frame both Reginald and Dick for the murder of the moneylender. Thankfully Farjeon does this by the midway point for the villains are so obvious the reader wonders why the police and everyone else can be so easily taken in by their machinations. Gracie isn't taken in but, of course, no one is going to believe a 12 year old girl. Except Dick Remington, that is. From its perfectly archetypal opening in which the characters are at the mercy of a menacing London fog to the perilous derring-do of Dick climbing a brick wall with rope and grapnel hook to the underhanded sleuthing of Detective Dennis Lambert of the Yard Samuel Boyd of Catchpole Square contains all that any reader has come to expect from a gaslight thriller.

With the revelation of the diabolical duo Samuel Boyd… becomes an all-out suspense thriller complete with cleverly handled courtroom sequences. The murder case becomes a cause célèbre attracting the attention of everyone in town including "members of the learned profession", actors actresses, writers and other celebrities along with merchants, housewives and their children. So crowded is the courtroom that some of the witnesses have to be escorted in from the hall. First we get a protracted inquest that frustrates coroner John Kent to distraction. The proceedings are hampered by a far too inquisitive jury member who is being goaded into asking intrusive, inappropriate and barely legal questions of several witnesses in order to sway the verdict towards implicating Reginald Boyd as the murderer. The novel ends in a climactic murder trial with the typical eleventh hour revelations including testimony from a French detective searching for an escaped master criminal and the unmasking of two characters’ dual identities.

One of the most intriguing incidents in the book from a history of the genre standpoint occurs when the two villainous doctors are fiddling with a newfangled camera of Dr. Pye's invention (see the illustration at left). It requires a strong burst from a magnesium flare and can illuminate the darkest unlit street from his second story study window. He has been photographing Samuel Boyd's house and has been seeing rather mysteriously the appearance of a face that resembles Boyd's even though he is dead. Pye then relates an anecdote about how useful and powerful the camera can be, especially in terms of "psychic photography". He asks his cohort, Dr. Vinser, to believe that a photographer friend of his used the camera to take a picture of a murder victim and when studying the photograph "...there under the lens of a powerful microscope was the portrait of the murderer upon the pupils of the dead man's eyes." The retained image, usually involving the retina not the pupils, on a corpse's eyes is a myth that shows up in late 19th century and early 20th century crime and detective fiction well into the 1930s, but this is the earliest recorded version I've come across. Apparently scientific fact is not the primary concern of these two doctors. But credit is due Farjeon with making these two doctors charlatans so we'll never know if he intended this sequence to be taken as satire of the gullible Victorian mind. Soon enough the reader learns the two men use phony titles to exert authority over others and have no background in medicine or science of any type.

But lapses into scientific myth aside if there is anything legitimate to criticize about Farjeon’s storytelling and writing it is his tendency to elevate his heroes and heroines to the status of sainthood while consigning his antagonists to behavior just shy of a mustache twirling and sneering vaudeville villain. From his very early career Farjeon modeled his work after that of Charles Dickens and we see in this late novel (he would write only three more books before he died in 1903) how he still aspires to the kind of triumphant overturning of detestable villainy by the virtuous and pure that was the hallmark of his idol. Rather than light touches of the sentimental paintbrush Farjeon slathers it on with sweeping broad strokes. Modern readers cry out for complexity and ambiguity in characters and incidents. You'll find no subtlety here. Even Dr. Vinsen, the more interesting villain of the two and seemingly modeled on Count Fosco ("My heart is large," says Vinsen obsequiously. "It bleeds for all"), has a sudden transformation within the span of a few sentences from sinister Machiavelli to cringing coward. But then sometimes it’s a welcome and refreshing change to know exactly who ought to get a rotten tomato thrown at him amid all the boisterous cheering for the good guys.

|

| B. L. Farjeon, at home, 1899 |

Those interested in reading Samuel Boyd of Catchpole Square have their choice of a variety of print on demand books (be warned of optical recognition transfers littered with typos!) and a couple of online versions that I investigated which conversely look to be well done. Copies of the actual book currently for sale are few and far between. I know that there were at least two editions in the UK from Hutchinson and one in the US from New Amsterdam Book Company. My copy is offset from the New Amsterdam edition and published by stalwart reprint house Grosset & Dunlap. It includes four glossy plates by Edith Leslie Lang, some are used to illustrate this post. Should you be lucky to find one a reading copy of Samuel Boyd... should cost you no more than $10 to $15 compared to a genuine UK first edition (Hutchinson, 1899) which in good to very good condition ranges from $46 to $150.

For an entertaining Victorian viewpoint of B.L. Farjeon's writing straight from the reader's pencil see this post on Curt Evans' blog where he shows us the written remarks made by a Victorian gentleman in his copy of Farjeon's other mammoth sensation novel Great Porter Square: A Mystery.

Vintage Mystery Reading Challenge update: L4 ("Man's name in the title") on the Golden Age card